Some Book Reviews

I noticed that there were two book reviews of the unified theory book

(http://www.unifiedtheoryofpsychology.com) and figured I would share them here…

>>>

Gregg Henriques is a young academic and clinical psychologist who has been working on this book for practically all of his (short) professional life. The result is terrifically challenging, to the point of perhaps being a new beginning for psychology as a research discipline.

The background fact is that all of the natural sciences have analytical cores that are taught in graduate schools around the world, and the various natural science disciplines are unified in the sense that where two disciplines overlap (e.g., quantum mechanics in physics and protein folding in biology) they agree on the basic analytical model. In the social sciences, only economics and behavioral biology have core theories, the former based on the Walrasian general equilibrium model, game theory, and the rational actor model, and the latter on evolutionary theory and population dynamics. Psychology is a particular mess, with lots of interesting contribution to a multifaceted body of research, but no underlying unity at all. Like sociology and anthropology, psychology is populated by a bunch of incompatible competing schools of thought.

Psychology, like sociology and anthropology, is not a mature science, because there is no sense in which each generation of researchers builds upon the core analytical insights of previous generations of researchers. In my book, The Bounds of Reason (Princeton, 2009) I offered a set of principles that might serve as the basis for the unification of all the behavioral sciences, with special emphasis on economic and sociology. Samuel Bowles and I published also published A Cooperative Species (Princeton, 2011), which effectively applied these principles to the integration of biology, anthropology, and economics. Gregg Henriques has now produced a credible core model for psychology that is synergistic with the principles I laid down in The Bounds of Reason and applied in A Cooperative Species.

This book is written for clinical and research psychologists, and hence avoids the sort of mathematical model building and axiomatization that is characteristic of mature sciences. In my review, I will suggest some ways his vision can be extended by focusing more intently on certain analytical issues. In this sense, I would have entitled the book “A Prolegomena to a Unified Theory of Psychology.”

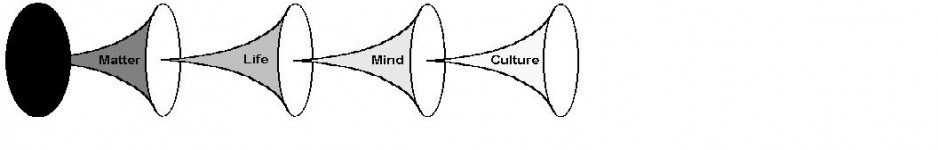

Henriques notes that it is almost impossible to define contemporary psychology because many psychologists consider psychology to be a theory of the workings of the mind, while others deny the notion of “mind” altogether, and limit themselves to modeling observed behavior. For this reason, Henriques takes his first goal to be that of “locating” the field ontologically. He argues that there is a Tree of Knowledge with four segments. The first is “Matter,” which is studied by physics, chemistry, geology, and astronomy. The second is “Life,” studied by biology. The third is “Mind,” which is the subject matter of psychology, and the fourth, and highest, is “Culture,” studied by the social sciences. Henriques pays special attention to the three points of junction between segments of the Tree of Knowledge. He says the Matter-Life junction is modeled by biological evolutionary theory, the Life-Mind junction is modeled by what he calls Behavioral Investment Theory, and the Mind-Culture junction is modeled by what he calls Justification Theory. By Behavioral Investment Theory, Henriques means essentially the rational choice model of decision, biological and economic theory, although he adds a dimension of complexity to human behavior by saying that Justification Theory requires a “rational emotional actor” that is not properly modeled in standard rational choice theory (p., 46). I might add that Henriques also includes game theory as part of Behavioral Investment Theory, simply because decision-making when there are multiple agents involved requires game-theoretic reasoning. This point of view is basic to economic theory. In biology, the extension of decision theory (e.g., foraging theory) to game theory was pioneered by John Maynard Smith, Evolution and the Theory of Games (Cambridge University Press, 1982), and now is standard in all of animal behavior theory.

In Henriques’ innovative terminology, social interactions are governed by an “Influence Matrix,” which is part of the psychology of the individual that regulates how the individual relates to others. Henriques stresses the emotional side of such interaction and avoids all game theoretic reasoning as well as any analysis of the role of incentives and payoffs in the choice of behaviors governed by the Influence Matrix. This part of his model should be analytically strengthened by adding standard epistemic game theory, as I try to do in The Bounds of Reason.

I believe Henriques’ espousal of Behavioral Investment Theory is the most important integrating concept in this book. If this principle alone were incorporated uniformly throughout research psychology, it would provide much of the sought-for analytical core. I am not equipped to assess its contribution to clinical psychology.

The Mind-Culture junction is the most problematical in Henriques’ core theory. Henriques argues that human culture is basically language, and humans invented language so they could “justify” their actions to others—this is Justification Theory. “Justification systems,” says Henriques (p. 113), “are the interlocking networks of language-based beliefs and values that function to legitimize a particular version of reality or worldview.” The concept is sufficiently broad as to encompass Einstein’s contributions to physics and Henriques’ explanation to his wife as to why he is late for dinner.

Henriques’ model of culture is a non-starter. First, much culture is fundamentally technological and non-linguistic, consisting of recipes for making tools and provisioning food. Even language has highly important functions beyond “justification,” including giving information, coordinating behavior, giving orders, making promises, praying to gods, singing songs, gossiping, and giving orders. Second, Mind is as much the product of Culture in humans as is the reverse. Certainly Henriques is correct in saying that minds developed biologically in many species long before culture emerged, and that the distinct psychological capacity of humans is to interrelate through cultural networks. However, gene-culture coevolutionary theory (see my paper, “Gene-culture Coevolution and the Nature of Human Sociality”, Proceedings of the Royal Society B 366 (2011):878-888) and the paleontological evidence (Robin Dunbar, Clive Gamble, and John Gowlett, Social Brain, Distributed Mind (Proceedings of the British Academy 2010) indicate that the human mind is a social mind that evolved through the background environment of human culture.

The Justification Hypothesis (language evolved to permit humans to justify their actions) is also probably a non-starter. There is a certain bottom line to human cooperation. In the long run, either you carry out your obligations or you do not. The idea that humans evolved the immensely complex and costly physiology of language vocalization and the energy-consuming vocalization areas of the brain in order to be able to better justify their failings is simply not plausible.

I do think, however, that there is a related evolutionary argument from Mind to Language (not Culture more generally). Human culture gave rise to tool-making in the pursuit of hunting animals. However, human hunting tools can be used to kill any man in his sleep, from afar, or simply by stealthy ambush. This is decidedly not the case in our primate relatives, where the alpha male in a hierarchical troupe can maintain his dominant almost exclusively by physical intimidation.

Tool-making thus doubtless gave rise to a crisis of governance in hominid societies. To fill the breech and individual with both high intelligence and a relatively advanced capacity to communicate verbally and facially would be vaulted to a leadership position in hunter-gatherer societies, he capacity to convince (justify?) being rewarded with high quality mates and more fit offspring.

What, then, do we do to repair the Mind-Culture junction? I propose that we refer back to human evolutionary theory, in which genes and culture coevolved, and culture is subject to an evolutionary dynamic much like that of genes. Indeed, culture is simply “epigenetic transmission” of information. According to this theory, genes are simply informational systems (sequences of base pairs in DNA that regulate protein formation) that are passed from generation to generation, and cultural systems are additional lines of informational transmission across generations. In this view, the Mind-Culture junction is actually further divided into Mind-Niche Construction-Culture, where Niche Construction is widespread in social species and accounts for important epigenetic information transfer across generations (see Kevin N. Laland and Marcus W. Feldman, Niche Construction, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004). For instance, bee hives and termite mounds persist across generations, and supply new generations with the information they need to survive and to perpetuate these structures.

A little additional speculation suggests that information theory lies at the basis of all stages of Henriques’ Tree of Knowledge. An important interpretation of quantum mechanical weirdness, in particular the ubiquity of observer effects, is that not only is matter energy, but energy and its distribution are explained by information theory. Similarly, life is organized information. A fully information-theoretic elaboration of the Tree of Knowledge might thus be attainable.

All very exciting.

>>>

You might not expect to find such detailed and practical information that applies to everyday life in a textbook, a psychology textbook no less, but it is in there. While this book is written for psyc grad students you don’t have to be one to appreciate and understand it (I am not), although you do need to be reasonably intelligent to follow the logic. The book presents a clear and coherent way of organizing essentially all knowledge, not just for the field of psychology. The Tree of Knowledge presented is both simplistic and super deep, you’ll be wondering why you didn’t think of it when you see it. Once the justification hypothesis is explained you will see how that affects essentially all human interactions and you will be the better for it. I loved learning about how people strive for power, love, and freedom and how each facet is a part of the overall equation. If you ponder the question of “are humans animals and if so where do they fit into the world” you will be pleased with the analysis presented here. If you go through life sort of “trying out” different philosophies and ideologies you will be hard pressed to find a more clear, logical, and defensible system of organization than you will find presented here. Bottom line, if you want to learn about life, the mind, humans and their culture and how it all relates, purchase this book and spend some time studying it, you won’t be disappointed. Plus you will be able to beat your friends in almost any debate you have after reading this treatise 🙂